by Serge Savard

The Université du Québec à Chicoutimi requires everyone at the end of his/her three-year outdoor leadership programme to undertake a major project. While looking at a map of the Maritimes, I had no hesitation in embarking upon a solo adventure that would take me across all of the straits on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The Strait of Belle Isle and Cabot Strait were two on the list, and they are not to be taken lightly. Both of them have a reputation that intimidates even fishers; one by reason of its distance, the other because of the huge volume of water it funnels through the narrow gap between Labrador and Newfoundland.

I have been sea kayaking professionally and for pleasure since 1995. My instructor role with the Canadian Recreational Canoeing Association has taken me on trips that allowed me to share my experiences and invigorate the kayaking community. Taking up the challenge of multiple Gulf crossings fit perfectly with my desire to validate and improve my knowledge of a sport which is accessible to all, but which also obliges one to respect its limits. Was I in a position to put into practice all of the precautions and safety measures required to succeed with this challenge?

It’s August 17 and I’m taking advantage of a wonderful day of surfing at Western Brook beach on the west coast of Newfoundland. The next day, I board the ferry at St. Barbe, bound for Blanc Sablon at full steam. The forecast window isn’t perfect. Twenty-five knot gusts stir my apprehension, but with a really early start in the morning, I will surely succeed in getting across the famous 18 nautical mile Strait of Belle Isle before Aeolus awakens.

August 19. Rising at 4:00 in the morning to dismantle my fragile camp, I quit the coast with a 10-knot westerly. On the other side of Île au Bois, the swell makes itself felt, but without any fanfare. Splashes of cold water from the Labrador Current cool my exertions, and hold me at a comfortable temperature. When Anchor Point appears on the horizon, a tidal current pushes me towards the north. I can monitor my progress with the GPS, and I correct my course on my compass in order to make up for lost time. At the mouth of the bay, the waves mount drastically, but not enough to stop me. I finally touch the ferry wharf 225 minutes later, and I have only a few steps to take to reach my vehicle.

August 22-24. I decide to start my crossing of Cabot Strait in Nova Scotia because the prevailing wind comes from the southwest. Strategic departure from the village of St. Lawrence Bay in order to take me to my first waypoint, St. Paul Island, nicknamed the “cemetery of the St. Lawrence.” My trip plan includes carrying enough drinking water to get me across the Strait, taking a day of rest on the island, and then paddling the 45 nautical miles separating Atlantic Cove from Port aux Basques. A southwest wind helps me reach St. Paul Island, 18 nautical miles from the shores of Cape Breton, but a strong tidal current makes me drift more than two nautical miles toward the Atlantic Ocean.

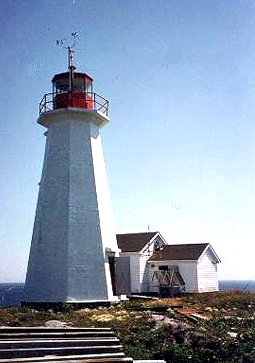

I arrive late in the day in a light, steamy fog. Grey abandoned buildings add to the eerie suspense that transfuses the morbid history of the island. There is only one place to land on the jagged shoreline, and taking advantage of a take-a-apart ladder belonging to the former radio station on the island, I climb up onto dry land to set up my camp. I can hear thunder throughout much of the night. My VHF radio provides weather forecasts as daylight looms. At 3:00 in the afternoon, I make the decision to do the crossing, even if a 10 to 15 knot easterly is forecast. Low tide will be at 6:30 p.m., so I leave the precarious safety of the coast at 6:00 p.m.

I have divided my route in the GPS database into four sections as a tactic to manage the psychological challenge of the crossing. After three hours of progress, a giant fog bank drapes itself over me. A miniature, portable light enables me to read my compass during the night. In thick, pea soup fog, this normally welcome technical aid, becomes a nightmare as it reduces my visibility to zero. A halo of white light envelops the compass, bright enough to give me a headache and impede my vision.

At exactly midnight, moonbeams escape their cloudy prison, and with perfect vision, my morale soars. On my right, another glow glistens on the strait, shining toward my craft – an approaching vessel of some kind. By following the series of red lights on the port side, and white at the bow of the cargo ship, I know that at this pace, our routes will surely cross. Noting the three lights the green, white and red of the ship – confirms my fear that I am not in a good spot. Soon, the immense metal hull is only about 500 metres away. My little carbon kayak will never withstand an impact with this vessel. But, taking advantage of my nimbleness and acceleration, I quickly get distance from it and its lights fades off into the darkness.

Nineteen nautical miles from Newfoundland, I spot the flash of the Cape Ray lighthouse. Gradually, one paddle stroke after another, I approach close enough to see the outline of the coast. My objective is the Marine Atlantic dock at Port aux Basques, which will make it easy for me to board the ferry for my return to North Sydney.

After 14 hours and 38 minutes and some 96 kilometres, I step foot on terre ferme once again. It will take another five hours for the effects of the heavy swell on my internal system of equilibrium to wear off. I am given a warm welcome by the ferry workers, but some of them have trouble believing that I have paddled across the Strait.

After two days of recuperation, I point myself towards Prince Edward Island in order to cross the Northumberland Strait, followed by the Straits of Honguedo and Jacques Cartier. There’s no rest for the wicked.

This experience has allowed me to validate several factors related to sea kayaking safety. The pursuit of the sport, at no matter what level of expertise, is facilitated by instruction that is adapted to the conditions you expect to paddle in. Learning under the supervision of experienced people is usually a positive investment. A kayaker can put new skills into practice and develop the judgement that is so precious in staying away from unnecessary trouble.

Serge would like to thank Kokatat and Mountain Equipment Co-op for their generous support for this expedition.

Reprinted from Ebb & Flow, Fall 2005, the newsletter of Kayak Newfoundland and Labrador. Photos courtesy of St. Paul Island Historical Society.